- Blog

- /

Now More Than Ever: Helping Women Facing Gender-Based Violence in Iraq

The COVID-19 pandemic has led governments around the world to issue stay-at-home orders, curfews and quarantine to contain the spread of the virus. For victims of domestic violence, this has meant being locked up with their abusers 24 hours a day, exacerbating threats to their safety and lives as stress and pressures mount at home. Victims of domestic violence are told if they leave their homes, they risk contracting COVID-19, but if they stay at home, they face beatings, rape, psychological abuse and domestic servitude.

How domestic violence manifests during COVID-19 varies around the world, informed by factors such as economic resources, culture, the status of women, access to legal protections and services, shelters, hotlines and counseling support. Similarly, how victims and their advocates, the courts, police, and medical providers respond to pleas for help during this period depends on available resources, restrictions on movement, government closures, and the political will to take violence against women seriously.

Sadly, Iraq is one of those countries where there was already a very weak response to violence against women when COVID-19 hit. In a country plagued by years of conflict, it is estimated that 14,000 women have been killed due to violence perpetrated by families, tribes, criminal gangs and militants. The Iraqi government does not gather statistics to document violence against women. However, in a survey conducted by the Ministry of Planning in 2012, 56% of men said they believed they had the right to beat disobedient wives. Women who were surveyed reported that in 75% of abuse cases the perpetrators were their husbands, and in 53% of the cases, their fathers.

This tragedy is exacerbated further by a legal system that shields perpetrators and lack of laws to protect victims of domestic violence, despite long-term efforts by advocates to pass such a law.

In addition, there is only one official shelter in Baghdad for women at risk of harm, and several unofficial shelters run by women’s organizations that cannot legally register because the government will not grant them permits. Therefore, women who flee family abuse are likely to end up in jail or trafficked on the streets. There are 16 Family Protection Units throughout the country that respond to calls from women for help, yet without meaningful options, many resort to encouraging women to reconcile with their abusers.

Iraqi women experience domestic violence within a communal and tribal culture and deal with multiple perpetrators in addition to abusive husbands. Many of these marriages are forced, which means they legitimated through rape and characterized by domestic servitude. Forced marriage and severe domestic violence lead women to commit suicide, seeing no other way out of the persecution they face every day. Because these cases are often handled within the family, where one or more relatives might intervene on behalf of a woman, movement restrictions are further isolating women from their limited sources of support.

One of the other tragedies of domestic violence in Iraq is that many cases are classified as suicides, when in fact they are homicides or coerced suicide, both of which are illegal under criminal law but are not always fully investigated and prosecuted. In just the last week, several deaths related to domestic violence were reported, including a 17-year old girl found hanging in Thi Qar, a suicide according to her husband. Without baseline data, it is impossible to know if cases are increasing due to pressures related to COVID-19 restrictions. However, given the rise in domestic violence around the world, one would expect Iraq to also follow this trend.

The importance of maintaining honor transcends all ethnic and religious groups and is a dominant force that leads families and tribes to impose a wide set of restrictions on their members. This has further implications during COVID-19 in at least some areas where conservative families refuse to allow female relatives to be tested, fearing they will be separated from the family and quarantined. Also, when families learn about quarantine conditions that violate cultural gender norms, they will not cooperate with the authorities.

Fortunately, there are small pockets of progress. In 2007, in the autonomous Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), the Ministry of Interior established a Directorate for Tracing Violence Against Women (DTVAW) followed by the opening of shelters in all three governorates. In 2017, 7,010 domestic violence calls came in from around the KRI. But since the start of COVID-19, curfews one month ago, DTVAW has reported a dramatic 75% drop in calls, suggesting that women could not find a safe place from which to call for help or inquire about their rights and options.

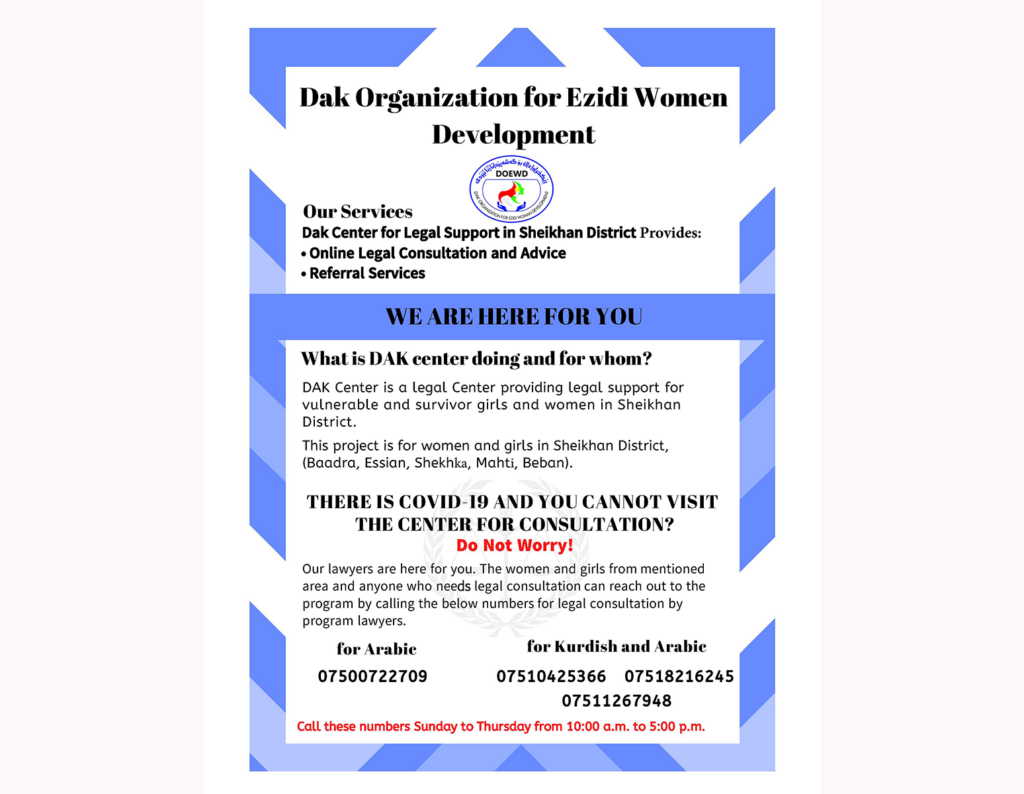

MSI is working with USAID to ensure that there are resources and protections in place for women and to find ways to support women during COVID-19. We are implementing the USAID Genocide Recovery and Persecution Response, Learning & Pilots project, a GBV pilot program in the Ninewa Plains in Iraq. It is focused on communities where predominantly ethnic and religious minority communities who were displaced by ISIS have returned and are trying to rebuild their communities. The program is working to help women recover from trauma and displacement and to respond to GBV through five innovative pilot programs, including legal and mental health and psychosocial support.

Because of movement restrictions and closure of courts and other government offices due to COVID-19, the project has adjusted to a remote program. Any services that can be conducted using phones or an online platform are continuing. Taking a GBV program online is sensitive given the risks to women who may be living with abusers, and extra care must be taken to ensure that women’s safety is not undermined in the course of providing services.

We are training and coaching partners about how to provide services, including how to conduct initial safety assessments. For example, social workers, lawyers and other staff are advised to confirm that women use their own phones; have a private space to talk, develop code words if someone walks into the room, and listen for cues that a woman is uncomfortable and may not be able to speak. After a phone or online call, providers can also remind women to take certain safety measures such as deleting text or call records.

This work is difficult under ideal circumstances where there are is going to require a lot of learning, adapting, and innovation. Most importantly, we will have to listen to the victims and survivors with whom we collaborate to find ways to survive and overcome abuse and persecution. At a time when the barriers just became so much greater, it is important to confront them and break them down.

Sitting back and waiting until this pandemic ends is not an option.